Fun with Numbers from the Daily Life of a Hobby Genealogist

The other day I was sitting in front of my family tree thinking: things are starting to get out of hand. I’ve managed to trace two of my ancestral lines back to the 11th and 13th centuries, respectively, and I haven’t been able to keep track of all my uncles and aunts since at least the 19th century. And then suddenly: wow, nobility in both branches! Okay, I kind of always knew that my graceful demeanor couldn’t have come from nowhere. Still, it was a pretty cool surprise. That led me to wonder how likely it really is to have noble ancestors. Naturally, I couldn’t ignore my curiosity and had to start calculating right away.

When the Ancestors Multiply Like Crazy

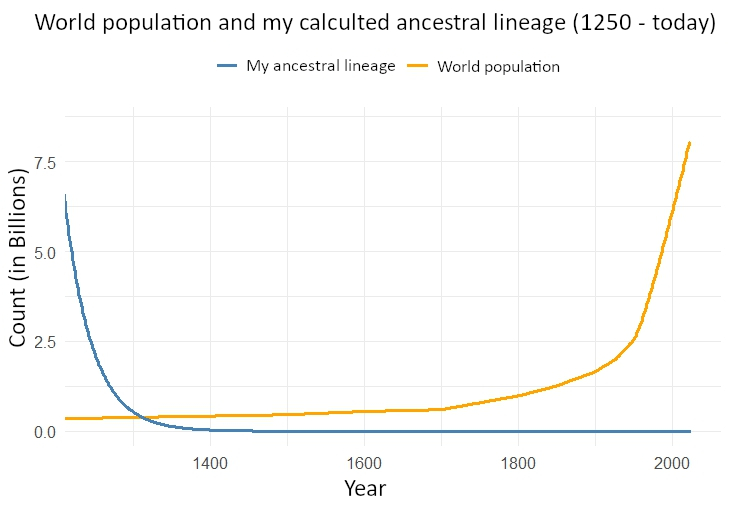

In every generation, the number of ancestors doubles: two parents, four grandparents, eight great-grandparents, simple enough. But after 20 generations (roughly 500 years), that’s over a million people. After 30 generations (about 750 years), it would be over a billion. The only problem: in the Middle Ages, the entire world didn’t even have that many people. Mathematically speaking, that means family lines inevitably overlap. Without what genealogists call pedigree collapse, the number of my theoretical ancestors would have exceeded the world’s total population as early as the 13th century. At some point, math runs out of space.

Example calculation:

1 generation ≈ 25 years

After 28 generations = 700 years

2²⁸ = 268,435,456

World population back then: about 350 million

Voilà, from that point on, statistically speaking, I’m related to everyone who lived at the time.

A Noble Gallery or Why I Feel Entitled to “Your Majesty”

But back to my digital noble family tree and my refined forebears: Ingelram de Balliol, Lord of Harcourt, Agnes of Cullen de Berkeley and the illustrious Eva FitzUchtred of Galloway, daughter of a half-Norwegian prince from southwestern Scotland.

And on the Saxon side, things are no less glamorous. Knightly families such as von Schleinitz, von Schönberg, von Kauffungen, Pflugk von Herden, and von Haugwitz, all noble, coat-of-arms-bearing, and firmly rooted in Saxon-Bohemian history.

So there I sat, surrounded by all this aristocratic prestige, debating where best to display the family crest and whether I should start asking my colleagues to address me as “Your Royal Majesty.”

Of course, I know that genealogical lines inevitably intersect. Even if you start with a few knights, every generation branches further until you inevitably end up with ordinary farmers, craftsmen, or nuns. Among the nobility, this was especially unavoidable, after all, people married within their class. The pool was limited, and a second cousin was often still considered a perfectly acceptable match. Some family branches intertwined again and again over generations, creating what genealogists call pedigree collapse: the same ancestors appearing multiple times, just on different branches of the tree.

In other words, the farther back you go, the fewer unique ancestors you actually have, even if the math suggests otherwise. Eventually, you start encountering the same knights, noblewomen, and landed gentry only rearranged in a slightly different order.

But the beautiful thing is this: you begin to experience history differently. Every name, every seal opens a window into a time when “von” meant something and when “data science” wasn’t yet a thing.

And Now It Gets Really Interesting

Mathematically speaking, and this is the fascinating part, all living humans share a Most Recent Common Ancestor (MRCA). Depending on the model, that person lived roughly 2,000 to 5,000 years ago, sometime during the rise of early civilizations in Mesopotamia or Egypt.

Go a bit further back, and you reach the Identical Ancestors Point (IAP), the point in time at which everyone alive who has living descendants today became an ancestor of everyone alive now. Estimates place this around 5,000 to 15,000 years ago. That means, if someone back then had children whose line never died out, then you (and I) are just as much descended from that person as every other human being on Earth.

Let’s run the numbers:

Average generation length ≈ 25 years

2,000 years ÷ 25 = 80 generations

2⁸⁰ = 1.2 × 10²⁴ possible ancestors

Even if every human who ever lived (about 110 billion) were included, that’s still only a tiny fraction of the total. So the mathematics of genealogy inevitably lead to one conclusion: Humanity is one big extended family. The more I research, the clearer it becomes. We’re all cousins, some through Scotland, others through Saxony, and others still through Mesopotamia. And that, really, is the most beautiful realization of all. Behind every coat of arms, castle, and title lies one vast, colorful family story that connects us all.

But enough of that. I’m off to hang my royal crest above the dishwasher. One must honor one’s heritage, after all. – By Maike Martina Heinrich – Nov 2025

Sources

Rohde, D. L. T., Olson, S., & Chang, J. T. (2004). Modelling the recent common ancestry of all living humans. Nature, 431(7008), 562–566.

UN Historical Population Estimates.

Wikipedia / Genealogisches Handbuch des Adels (Families Schleinitz, Schönberg, Haugwitz).

World population estimates according to Maddison Project Database (2020).