Star Trek and the Real Quest for Clean Fusion Energy

“Deuterium injection active – plasma flow stable!” – If that line immediately conjures up the image of a vertically mounted warp core glowing with blue plasma gas in the engineering section of an Intrepid-class starship, congrats, you’re a nerd. In the Star Trek universe, it’s especially the Voyager series of the 1990s that gives us a detailed look at this fascinating piece of future technology. Infinite space, reachable and explorable thanks to warp drive, a reactor that merges matter and antimatter in a controlled way to produce energy on a previously unimaginable scale. But how far-fetched is all of this, really? What’s science fiction, and what’s genuine modern fusion research? Let’s compare.

| Aspect | Star Trek | Reality |

| Fuel | Deuterium (from water) | Deuterium & Tritium (from water & lithium) |

| Reaction | Fusion / Matter–Antimatter | Fusion (Deuterium–Tritium) |

| Plasma | Controlled & channeled by magnetic fields | Likewise: magnetic confinement in tokamaks / stellarators |

| Energy efficiency | Nearly 100 % utilization | Theoretically possible, practically still < 1 % |

| Waste | No radioactive waste | Only short-lived neutron activation |

| Scale | Starship propulsion | Stationary reactor |

What was once science fiction is now within reach through real-world fusion research. Deuterium, the “heavy hydrogen” that Voyager uses as fuel, is no fantasy. It’s a real isotope of hydrogen found in ordinary water: about every 6,000th hydrogen atom is a deuterium nucleus with an additional neutron. In modern fusion reactors, such as ITER in France, Wendelstein 7-X in Greifswald, Germany, or the National Ignition Facility in the U.S., deuterium is combined with tritium, another hydrogen isotope containing two neutrons.

The two react according to the formula:

D + T → He⁴ + n + 17.6 MeV

That means deuterium and tritium fuse into a helium nucleus (He⁴) and a high-energy neutron.

The reaction releases an enormous amount of energy, about four million times more per kilogram of fuel than chemical combustion. To make this reaction possible at all, the hydrogen isotopes must be brought into a state where their electrons are stripped away:

Plasma. Yes, just like the shimmering blue soup inside the warp core.

Plasma is a gas of free nuclei and electrons, electrically conductive and extremely hot. In a fusion reactor, this plasma is heated to over 100 million °C, hotter than the core of the Sun. Only under these conditions can the positively charged nuclei overcome their mutual repulsion and fuse.

To prevent the plasma from destroying the reactor wall, it’s confined and stabilized by strong magnetic fields in a ring-shaped chamber, similar to the “magnetic deuterium-flow conduits” on Voyager. What Voyager calls EPS conduits and warp-plasma flows are known in the lab simply as tokamak coils or stellarator fields. And even if no one in the control room shouts “Plasma flow stable!”, that’s essentially what’s happening.

For two atomic nuclei to fuse, they must overcome immense repulsive forces, achievable only at those extreme temperatures beyond 100 million °C. In the ring-shaped magnetic fields of a tokamak (ITER) or stellarator (Wendelstein), the plasma is confined to minimize energy loss.

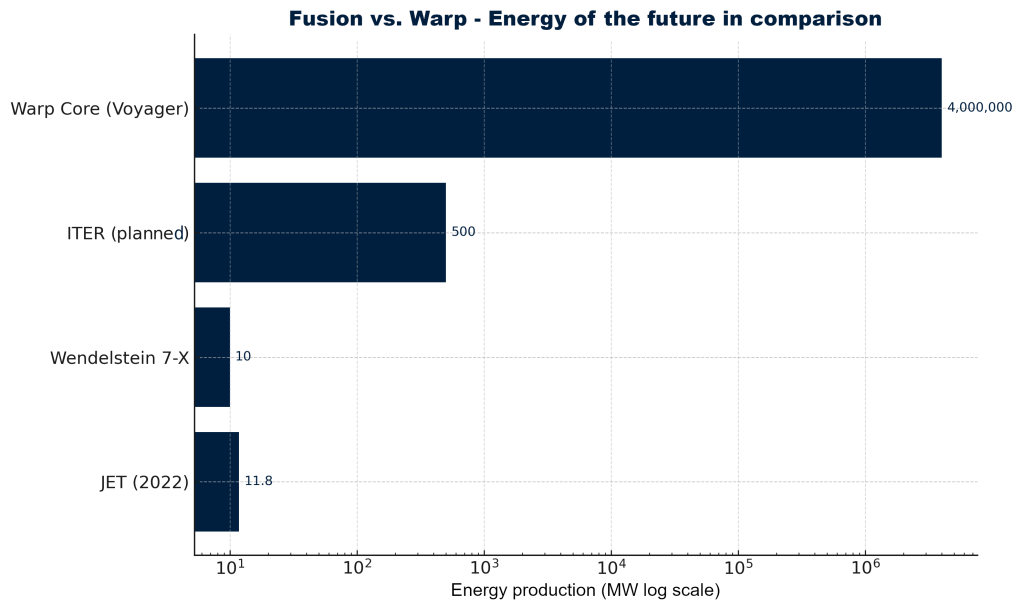

It’s a technical masterpiece, a miniature star on Earth. The greatest challenge is to maintain this state stably so that energy output exceeds input. ITER aims to generate more energy than it consumes in the 2030s: 50 megawatts in, 500 megawatts out, a milestone scientists call ignition. On December 5 2022, the U.S. facility NIF achieved a symbolic breakthrough, producing 3.15 megajoules of fusion energy from 2.05 MJ of laser input, still far from a warp core, but a historic step nonetheless.

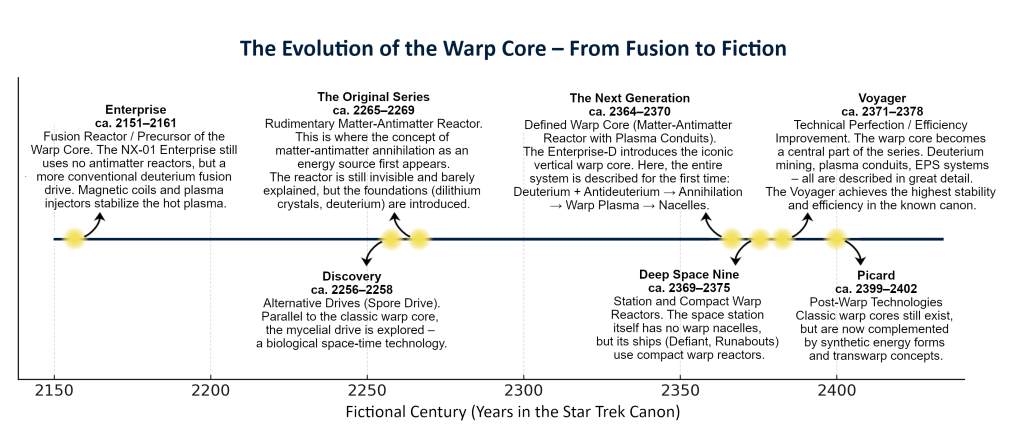

The idea of converting matter into energy in a controlled way predates Voyager, it’s the backbone of the entire Star Trek universe. Yet only over decades did a vague concept evolve into a detailed technical system.

The early series knew only the general idea of a matter–antimatter reactor.

In The Next Generation (1987–1994), the warp core was systematically described for the first time: Deuterium and antideuterium are injected into a reaction chamber, where their energy release is stabilized by dilithium crystals. The resulting warp plasma flows through EPS conduits to the warp nacelles, where it warps spacetime, and suddenly, faster-than-light travel.

Voyager brought this physics to perfection: recurring overloads, deuterium collection, efficiency issues, all realistic and technically consistent. And Enterprise (2001–2005) later portrayed the most plausible early form: pure deuterium fusion without antimatter, almost real science. So how close is humanity actually to a warp core?

The warp core remains beyond human reach, but the underlying idea, controlled deuterium fusion, is real. Terms like plasma flow, magnetic coils, or deuterium injection are no longer pure science-fiction jargon; they describe genuine physical processes in fusion labs on Earth. What glows inside Voyager shines today in Cadarache or Greifswald as magnetically confined miniature suns. But we never really needed anyone to tell us that Star Trek was only entertainment. We always knew it was visionary, brimming with scientific optimism. The notion that a starship, or perhaps one day an entire planet, could be powered by energy drawn from water connects science and science fiction like almost nothing else. Today, more than half a century after Captain Kirk’s first voyage, humanity is actually researching energy sources based on the same principles.

Perhaps soon the day will come when we travel at warp 1, the speed of light, or even faster through our galaxy, to explore strange new worlds, to seek out new life and new civilizations, and to boldly go where no one has gone before…

P.S. For the die-hard fans: a quick rundown of warp propulsion through Star Trek history

The Original Series (1966–1969)

Technical level: rudimentary. In the original series, “warp drive” was more a plot device than a defined system. People spoke of the matter–antimatter reactor and dilithium crystals, but details were vague. The reactor itself remained off-screen and barely depicted. Deuterium was mentioned but never explained. “Warp engines offline” was purely dramatic, not technical. Conclusion: The idea existed, but there was no defined “warp core.”

The Next Generation (1987–1994)

Technical level: advanced — here the modern warp core was born. Introduction of the vertical warp core, visible in the Enterprise-D’s engineering set. The first official schematic appeared in Star Trek: The Next Generation Technical Manual (Rick Sternbach & Michael Okuda, 1991). Operating principle: Reaction of deuterium (matter) and antideuterium (antimatter); dilithium crystals as regulator (stabilizing the annihilation); energy → warp plasma → EPS conduits → warp nacelles. Many terms later adopted by Voyager originated here: warp plasma, matter injector, magnetic constriction. Conclusion: TNG marks the “birth of plausible warp physics” in the franchise.

Deep Space Nine (1993–1999)

Technical level: stable but backgrounded. Focus on the space station — no central warp core. Runabouts and the Defiant still use deuterium/antimatter reactors. Smaller ships = more compact reactors, same physics. Conclusion: Same technology, less screen time — a bit more soap opera in space.

Voyager (1995–2001)

Technical level: fully realized. Here, the warp core is a central plot element — overloads, sabotage, energy crises. B’Elanna Torres and Harry Kim regularly discuss technical parameters. Deuterium is explicitly called an “everyday fuel” (episode Demon, S4E24: Voyager lands on a planet to mine deuterium). Warp-plasma conduits, EPS systems, and antimatter containment are all explained in detail. “We’re losing containment on the antimatter injectors!” — a classic line that’s even somewhat physically plausible. Conclusion: Voyager is the engineers’ series of the franchise — the most consistent and technically detailed. (No secret which one’s my favorite.)

Enterprise (2001–2005)

Technical level: prototypical. Set before Kirk, showing the early Warp 5 Engine. No classical antimatter reactors yet — instead, conventional fusion reactors using deuterium plasma. Introduction of plasma injectors and magnetic coils, precursors of the Next Generation system. Conclusion: Very close to real fusion physics — almost a realistic prequel to the warp era.

Discovery and later series

Technical level: extended concepts. Discovery introduces the spore drive — no longer physics, but metaphor. Picard and Prodigy still reference traditional warp cores as standard technology. Conclusion: The warp core remains the foundation, but newer shows transcend physics toward metaphors of connection, consciousness, and beyond.

– By Maike Martina Heinrich – Nov 2025.

Sources

Curry, D. (2003). Interview in Star Trek Communicator Magazine (No. 145). Titan Magazines.

ITER Organization (2025). Project Data Overview. https://www.iter.org

Jenkins, H. (1992). Textual Poachers: Television Fans and Participatory Culture. Routledge.

Johnson-Smith, J. (2005). American Science Fiction TV: Star Trek, Stargate and Beyond. I. B. Tauris.

Max-Planck-Institut für Plasmaphysik (2025). Wendelstein 7-X Project. https://www.ipp.mpg.de/w7x

Memory Alpha. (n.d.). NX-class starship. In Memory Alpha: The Star Trek Wiki. Fandom. Retrieved October 21, 2025, from https://memory-alpha.fandom.com/wiki/NX_class_starship

Memory Alpha. (n.d.). Spore drive. In Memory Alpha: The Star Trek Wiki. Fandom. Retrieved October 21, 2025, from https://memory-alpha.fandom.com/wiki/Spore_drive

Memory Alpha. (n.d.). Warp core. In Memory Alpha: The Star Trek Wiki. Fandom. Retrieved October 21, 2025, from https://memory-alpha.fandom.com/wiki/Warp_core

Okuda, M., & Okuda, D. (1996). Star Trek Chronology: The History of the Future (2nd ed.). Pocket Books.

Okuda, M., Okuda, D., & Mirek, D. (1999). Star Trek Encyclopedia: A Reference Guide to the Future. Pocket Books.

Sternbach, R., & Drexler, D. (1998). Star Trek: Deep Space Nine Technical Manual. Pocket Books.

Sternbach, R., & Okuda, M. (1991). Star Trek: The Next Generation Technical Manual. Pocket Books.