Why dating apps promise matches but sell subscriptions

The logic of the swipe

It begins with a small gesture. A swipe to the right, and somewhere out there someone might do the same. That moment, that tiny click, has become a symbol of our modern longing: the hope that an algorithm knows what our heart wants. Never before has the choice been so vast, closeness so convenient, the promise so mathematical. Billions of data points, artificial intelligence, matching scores. And yet the outcome often feels all too human: ghosting, exhaustion, endless chats without a meeting. The paradox is obvious. If dating apps were truly successful, they would put themselves out of business. Their business model does not live on love but on the search for it. They make money as long as you hope, not when you find.

Behind the glowing icons on our phones there is no machine of romance, but a sophisticated system of behavioral data, probabilities and monetary targets. And this system is programmed for something that does not know love: engagement. The longer you stay, the better the code performs.

The machine behind the longing

At their core, dating apps are recommender systems, the same technology that decides what you watch next on Netflix or which product you might like on Amazon. The difference is that we are not recommending shows but people. Formally it works like this. For every profile you could see, the algorithm estimates the probability that you will interact, that you will like, reply or chat. This probability is based on everything you have done so far, whom you liked, how long you linger on photos, when you tap or scroll on. The result is a ranking optimized for predictive accuracy, not for compatibility, not for happiness, but for behavioral probability. This reflects the typical optimization logic in recommender systems, which are empirically known to maximize engagement rather than emotional well-being, though the exact objective functions of commercial apps are not publicly verifiable. You do not see the people who fit you best. You see those who are most likely to continue your current behavior. The system learns. It watches you, adapts, tests variants. In the field this is called exploration versus exploitation. Exploration means showing you new and perhaps atypical suggestions. Exploitation means keeping you with what you like anyway. Over time the balance shifts. The system learns what keeps you engaged the longest, and that becomes the priority. A quiet, algorithmic filter bubble of attractiveness emerges. It sharpens your taste and narrows it at the same time.

Philosophically this is fascinating. The machine does not know what love is. But it does know how you behave when you believe you are getting close to it. It does not reproduce your desire but the trace it leaves in the data.

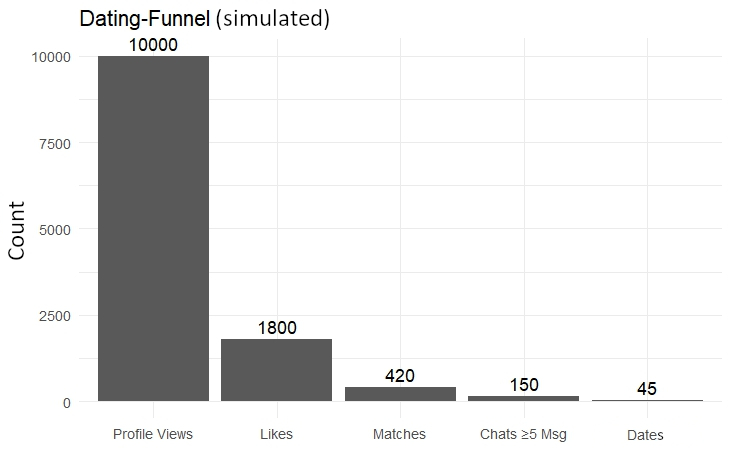

The following plot shows how drastically attention thins out along the typical usage chain. Thousands of profile views lead to a few likes, even fewer matches, and only a tiny fraction turns into real conversations or meetings. The system thrives on the top of the funnel, on clicks, swipes and micro-moments, not on what happens at the end.

Follow the money – How dating apps do not sell love but hope

It sounds romantic. Find your great love with a single swipe. Behind that promise lies one of the most profitable business models in the digital world. The big dating apps do not live on happy couples but on people who are searching, though no company explicitly states this as a policy. But the principle is simple and effective. Entry is free, the classic freemium model. If you want to see who liked you, be more visible or get more matches, you pay. There are boosts, super likes, premium filters or gold subscriptions. Investors call these features conversion points, moments in which an emotional impulse turns into revenue. The longer you hope, the better for the algorithm and the company. Love is not the goal but the story that keeps the engine running.

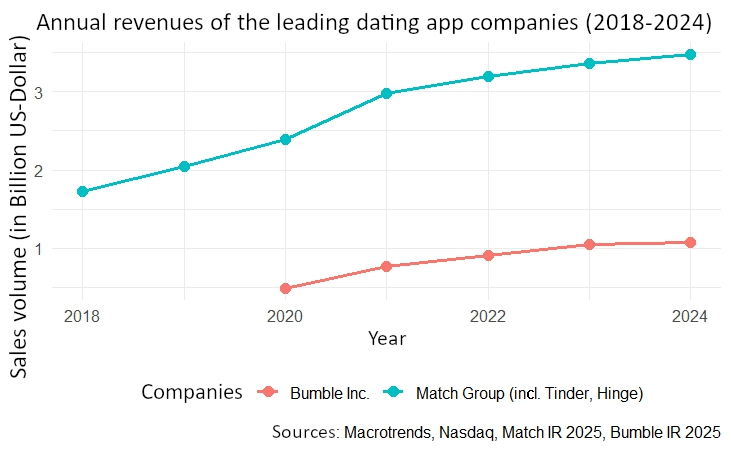

The scale is enormous. Match Group, which includes Tinder, Hinge, OkCupid and others, increased annual revenue from about 1.73 billion US dollars in 2018 to about 3.48 billion US dollars in 2024 (Macrotrends, 2025; Match IR, 2025). Bumble Inc., publicly listed since 2021, grew in the same period from 582 million US dollars in 2020 to 1.07 billion US dollars in 2024 (Macrotrends, 2025; Bumble IR, 2025). Both companies show steady growth over years, with a visibly flattening dynamic since 2023, consistent with investor commentary about market saturation and limited user growth. The platforms reach few new users and the number of paying customers stagnates. Investor reports and industry analyses show that companies therefore rely more heavily on price increases, add-on features and algorithmic visibility advantages to drive further growth. Match Group’s 2024 executive commentary explicitly mentions merchandising, à-la-carte features, and price optimization to increase revenue per payer, which supports this interpretation

The following plot uses the published yearly figures from 2018 to 2024. It shows strong growth until 2022 and then a phase of slower expansion, a sign that the business of love may be approaching its economic peak.

Company reports explicitly discuss pricing optimization and revenue per payer growth (SEC, 2023). These systems are designed to keep you engaged yet dissatisfied enough to pay and to return. A successful algorithm gives you just enough matches to spark hope, but not enough to make you leave.

One might say the machine does not know what it optimizes. It cannot see the spark between two people. It only sees correlations between clicks. In training data those who reply frequently count as compatible. Frequent replies only show that two people behave well inside the system, not that they fit each other.

Trade-off as a model

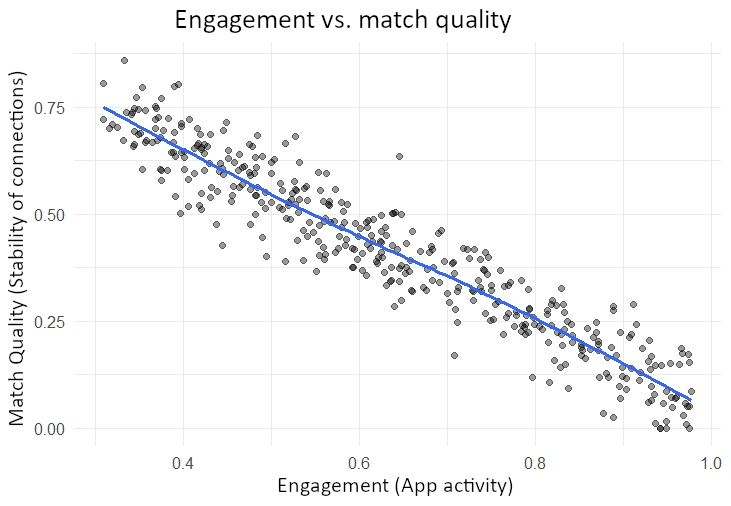

This contradiction can also be shown graphically. If you look at the relationship between engagement, the activity inside the app, and match quality, the depth and stability of connections, a clear pattern emerges. As an algorithm drives more time and interaction, the average depth of connections declines. The following graphic shows this trade-off. Engagement is on the horizontal axis, match quality on the vertical axis. The curve drops visibly. With each increase in activity the system loses some of its ability to foster real closeness. Even a perfect algorithm cannot optimize for short-term stimulation and long-term compatibility at the same time. It has to choose, and in practice it almost always chooses what is measurable, interaction. Clicks can be counted. Feelings cannot.

Bias and social feedback – How algorithms reproduce beauty, power and visibility

Scroll long enough through dating apps and it can feel as if the system is conspiring against you. Some profiles appear constantly, others never. Young and conventionally attractive people receive likes by the second, while others remain almost invisible. This is not coincidence but statistics. The algorithm is designed for efficiency. It shows those with the highest probability of a match. That probability is based on past behavior and with it on the biases of the crowd. If a group is liked less often, its visibility drops. Lower visibility means fewer chances for matches. Fewer matches then confirm to the system that this group is less popular. A self-fulfilling bias emerges.

The feedback effect in numbers

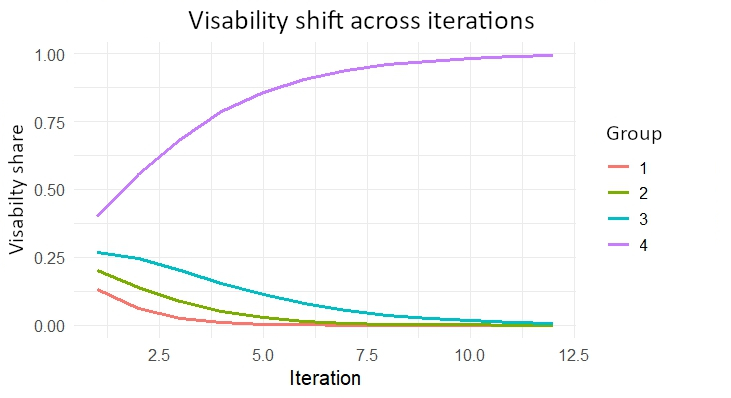

You can simulate this in a simplified but telling way. Imagine four user groups with slightly different reply probabilities. At first all groups are equally visible. As soon as the system weights visibility by past success the balance tilts and small differences become large inequalities. A small initial advantage, such as adherence to an attractiveness norm, skin color, age or gender, can multiply in just a few iterations. The algorithm is not “against” any group, but it amplifies existing social preferences because it learns them as patterns of success.

From preference to discrimination

Empirical analyses show exactly this, most prominently in OkCupid’s 2009–2014 data, which revealed lower reply rates to Black women and Asian men (Rudder, 2014; Gwern, 2014). More recent regulatory and research cases, such as the Dutch Breeze investigation (de Jonge & Zuiderveen Borgesius, 2024), indicate that algorithmic bias remains an active issue. These data are not invented, they come from billions of real interactions. Sociologists describe such processes as algorithmic sedimentation. Prejudices harden, become invisible, technical and thus appear neutral even though they are not. Philosophically this is a structural misunderstanding. What occurs frequently is interpreted as natural, although frequency often reflects social inequality.

The ethics of the match

This is where the ethical fault line lies. The system promises closeness, but closeness that lasts is bad for business. A real match that leads to love is economically counterproductive. The machine therefore produces many small beginnings rather than one great outcome. It sells us the possibility of starting again and again. One could say Tinder is the marketplace of the eternal beginning. In the vocabulary of Jürgen Habermas, the life-world of love is colonized by the system logic of capital. Communicative rationality, the honest exchange between two subjects, is replaced by instrumental rationality. How do I optimize my profile. How do I keep someone interested. How do I increase my visibility. The system turns us into strategists rather than lovers. Jean Baudrillard would have seen a perfect simulation in all this, a world in which signs lose their reference and only refer to each other. The match becomes the sign of love without love, a symbol that circulates until it is taken for real. The tragic and perhaps the beautiful part is that even within this simulation the human core remains. We long, doubt, hope and disappoint one another. Sometimes, against all odds,a match does lead to a real person, to a real meeting. Then the code collapses into reality and for a moment the unpredictable wins. A match is neither a lie nor the truth. It is a tool, a mathematically generated impulse that addresses our need for connection. What we make of it is our responsibility. Perhaps that is the true mathematics of love, not calculating the probability of finding someone, but having the courage not to be defined by probability.

Beyond the swipe – What a humane design of love could look like, and why it may never exist

It is easy to condemn dating apps. The truth is more complex. They address a real need. Loneliness, curiosity, the longing for closeness are not errors but some of the most human constants of our time. The problem is not the need but the system that exploits it. If machines mediate relationships, we should judge them by what they foster. Do they foster encounters or attachment. Self-display or self-knowledge. Efficiency or empathy. Today the target function is clear, engagement. We could define other metrics. Not how long someone stays in the app, but how often someone leaves because they have found what they were looking for.

Research on humane recommender systems increasingly discusses outcome metrics. How many conversations last more than ten messages. How many encounters lead to genuine contact. How many pairs still write after a month. This sounds simple but it is a paradigm shift. We would not optimize for clicks but for continuity. We would not measure attention but relationship. Such a system would be less attractive economically and more meaningful for people. It would have fewer users but perhaps more who stay because they do not have to search anymore.

The design of friction

Humane design needs friction. Instant gratification through swiping is psychologically efficient and emotionally shallow. An ethical platform would build in slowness. Limited daily matches. Algorithmic pauses to encourage reflection. Hints toward conversation quality rather than profile performance. In UX research this is called friction design, deliberate interruptions that help users step out of automatic behavior. Love does not begin in reflex but in decision. – By Maike Martina Heinrich – Nov 2025.

Cover Photo: Chen, Unsplash

References

Abeliuk, A., Elbassioni, K., Rahwan, T., Cebrian, M., & Rahwan, I. (2019). Price of Anarchy in Algorithmic Matching of Romantic Partners. arXiv Preprint. https://arxiv.org/abs/1901.03192

Backlinko. (2024). Bumble User Statistics – Usage and Revenue Data. Abgerufen von https://backlinko.com/bumble-users

Baudrillard, J. (1981). Simulacres et Simulation. Paris: Éditions Galilée. — sinngemäß zitiert zu „Simulation von Nähe“.

Bauman, Z. (2003). Liquid Love: On the Frailty of Human Bonds. Cambridge: Polity Press. — Bezug auf „flüchtige Liebe in der Moderne“.

Bumble Inc. (2025). Fourth Quarter and Full Year 2024 Results – Investor Press Release. Austin, TX. Abgerufen von https://ir.bumble.com/news/news-details/2025/Bumble-Inc.-Announces-Fourth-Quarter-and-Full-Year-2024-Results/

de Jonge, T., & Zuiderveen Borgesius, F. (2024). Mitigating Digital Discrimination in Dating Apps – The Dutch Breeze Case. arXiv Preprint. https://arxiv.org/abs/2409.15828

ElectroIQ. (2024). Online Dating Industry Statistics and Market Overview 2024. Abgerufen von https://electroiq.com/stats/online-dating-statistics/

Feliciano, C., Robnett, B., & Komaie, G. (2009). Gendered racial exclusion among white internet daters. Social Science Research, 38(1), 39–54. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ssresearch.2008.09.004

Goodhart, C. A. E. (1975). Problems of Monetary Management: The UK Experience. In Papers in Monetary Economics (Vol. 1). Sydney: Reserve Bank of Australia.

Gwern. (2014). Race and Attraction (OkCupid Data 2009–2014). https://gwern.net/doc/psychology/okcupid/raceandattraction20092014.html

Habermas, J. (1981). Theorie des kommunikativen Handelns (Bd. 1 & 2). Frankfurt am Main: Suhrkamp.

Hitsch, G. J., Hortaçsu, A., & Ariely, D. (2010). What makes you click? Mate preferences in online dating. Quantitative Marketing and Economics, 8(4), 393–427. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11129-010-9088-6

Lin, K.-H., Lundquist, J. (2013). Mate Selection in Cyberspace: The Intersection of Race, Gender, and Education. American Journal of Sociology, 119(1), 183–215.

https://doi.org/10.1086/673129https://doi.org/10.1177/2378023120956412

Match Group, Inc. (2025). Form 10-K Annual Report for the Fiscal Year Ended December 31, 2024. U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission (Filing No. 0000891103-25-000027). Abgerufen von https://www.sec.gov/ix?doc=/Archives/edgar/data/891103/000089110325000027/mtch-20241231.htm

Match Group, Inc. (2025). Q4 2024 Shareholder Letter & Executive Commentary. Dallas, TX. Abgerufen von https://s203.q4cdn.com/993464185/files/doc_financials/2024/q4/Q4-2024-Executive-Commentary_vF.pdf

Rudder, C. (2014). Dataclysm: Love, sex, race, and identity–What our online lives tell us about our offline selves. Crown.

Start.io. (2024). Tinder App Dominates U.S. Dating App Market While Bumble Tumbles. Abgerufen von https://www.start.io/blog/new-data-tinder-app-dominates-u-s-dating-app-market-while-bumble-tumbles

The Society Pages. (2017). Race, Gender and Likes on OkCupid. https://thesocietypages.org/socimages/2017/03/31/race-gender-and-likes-on-okcupid/

Wang, H. (2023). Algorithmic Colonization of Love: The Ethical Challenges of Dating App Algorithms in the Age of AI. Techné: Research in Philosophy & Technology, 27(2), 260–280.