Which factors shape how satisfied we are with our lives

Some people are more satisfied with their overall life situation than others. This becomes clear in data from the European Social Survey (ESS), which has been regularly collecting information across Europe for more than twenty years, on people’s lives, health, and attitudes. But how can these differences be explained? A closer look at several potentially relevant factors helps to shed light on this question.

Freedom makes people happy – but not alone

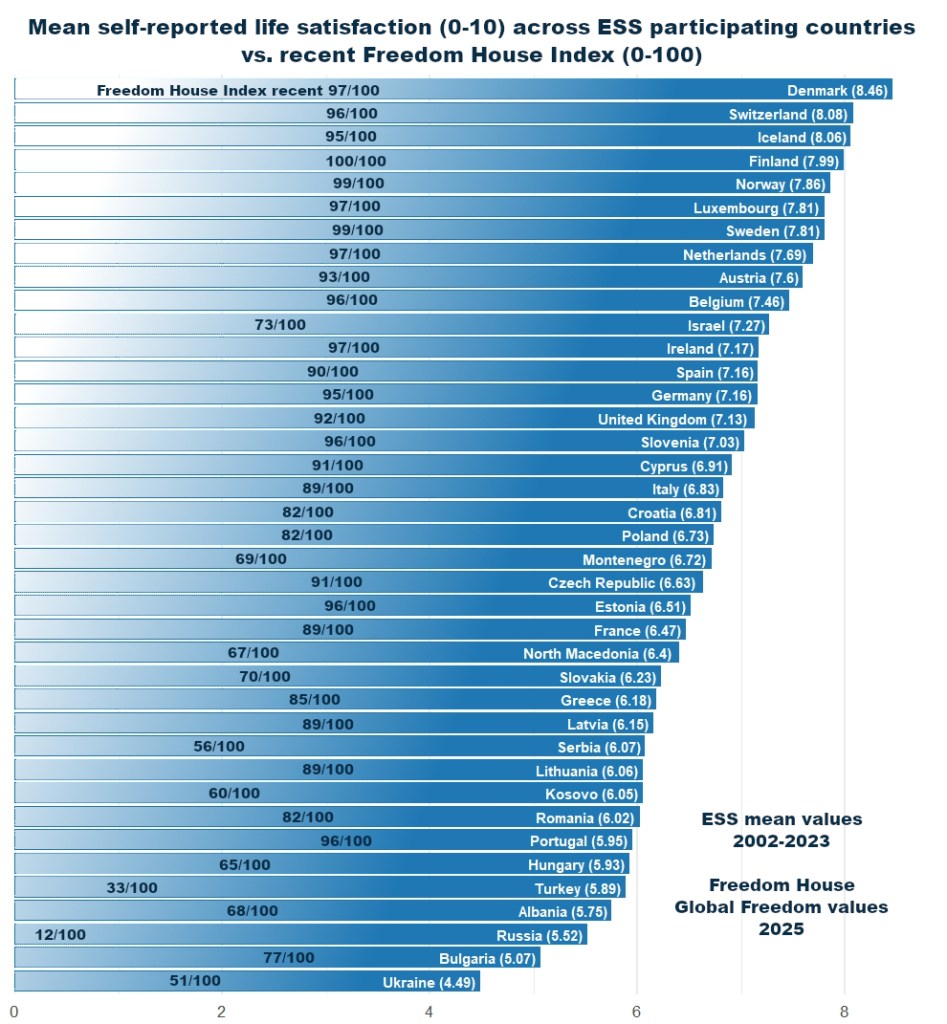

For the following overview, responses on life satisfaction were averaged across all available ESS rounds and compared with the current Freedom House Index for political and civil liberties. The result is striking: The freer a country, the more satisfied its citizens tend to be.

At the top of the ranking are the Nordic countries. Denmark, Switzerland, Iceland, Finland, and Norway, with average life satisfaction scores around eight points and almost perfect freedom scores between 95 and 100. These nations combine stable democracies with strong social safety nets, institutional trust, and a high standard of living, conditions that seem to create particularly favorable environments for people to experience their lives as fulfilling.

In the middle range are countries like Germany, Spain, Italy, and Croatia: all classified as free, yet with only moderate satisfaction levels between six and seven points. Here it becomes clear that formal freedom alone is not enough. Economic inequality, high living costs, or social tensions can lower well-being even in consolidated democracies.

At the lower end of the scale are mostly Southeast and Eastern European as well as post-Soviet states – such as Albania, Bulgaria, Russia, and Ukraine. People there report the lowest levels of life satisfaction, and at the same time, political rights, media freedom, and the rule of law are most restricted. The pattern is unmistakable: Limited freedom, weak institutions, and ongoing insecurity generally go hand in hand with lower well-being.

A few countries stand out. Portugal and France, for instance, score slightly below the European trend despite high levels of freedom. Economic crises, social tensions, or political dissatisfaction may play a role here. Israel, too, shows somewhat lower life satisfaction despite relatively strong democratic structures, perhaps reflecting current political and social conflicts.

Country life tends to make people happier

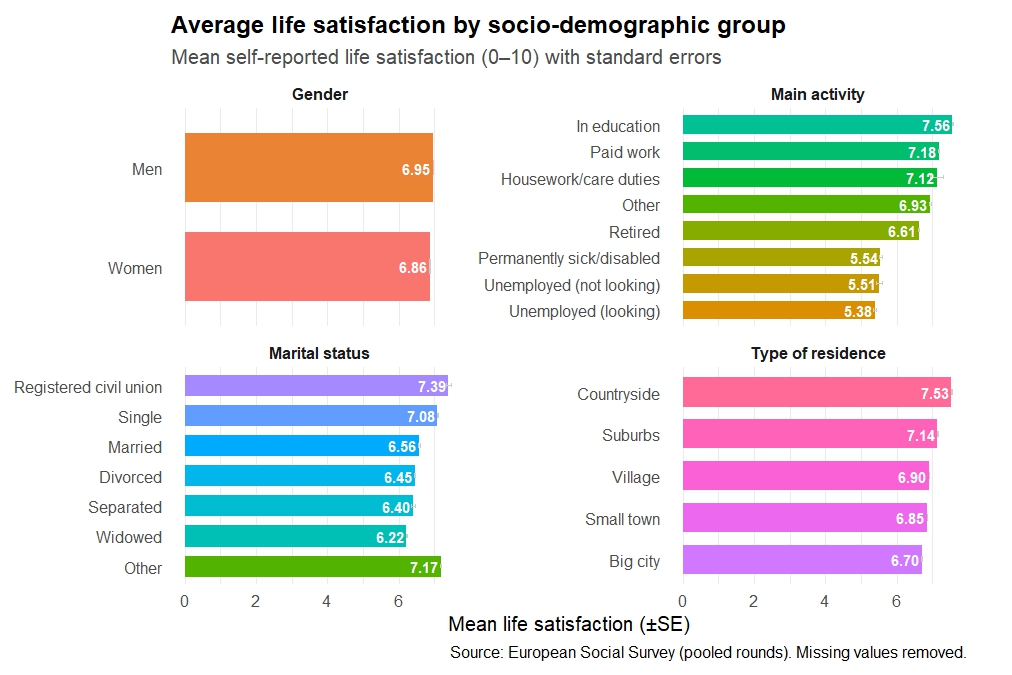

Political and personal freedom may thus be an important framework for quality of life, but that is not the whole story. A closer look at ESS data shows that life satisfaction also varies within societies. Age, income, and education certainly matter, but so do place of residence, employment status, and family situation.

The results reveal a clear pattern: People living in rural areas are the most satisfied. On average, they rate their lives at 7.5 points, noticeably higher than city dwellers (6.7 points). This suggests that peace, nature, lower living costs, and stronger community ties may foster greater well-being in the countryside, whereas urban life, while full of opportunity, often brings stress, anonymity, and financial pressure.

Relationships make happy

Differences also appear by marital status. People living in partnerships or civil unions report the highest satisfaction (7.4 points), while widowed, divorced, or separated individuals score clearly lower. This reflects the importance of social bonds: those in stable relationships tend to experience more emotional support and security, two key components of subjective well-being.

When it comes to main activity, students and employed people score the highest (between 7.1 and 7.6). At the bottom are those who are permanently ill or unemployed. This is not surprising, employment brings not only income but also structure, social participation, and a sense of agency, while illness and joblessness often lead to isolation and loss of control.

Men remain slightly more satisfied than women

Gender differences, by contrast, are minimal: men (6.95) and women (6.86) report almost equal levels of satisfaction. This tiny gap suggests that life satisfaction in Europe has largely equalized between men and women, likely due to social changes over recent decades.

Overall, the data paint a coherent picture: satisfaction arises where stability, social connection, and a sense of meaning come together. People who perceive their lives as stable and self-determined are significantly more satisfied, regardless of gender, but strongly influenced by relationships, health, and social participation.

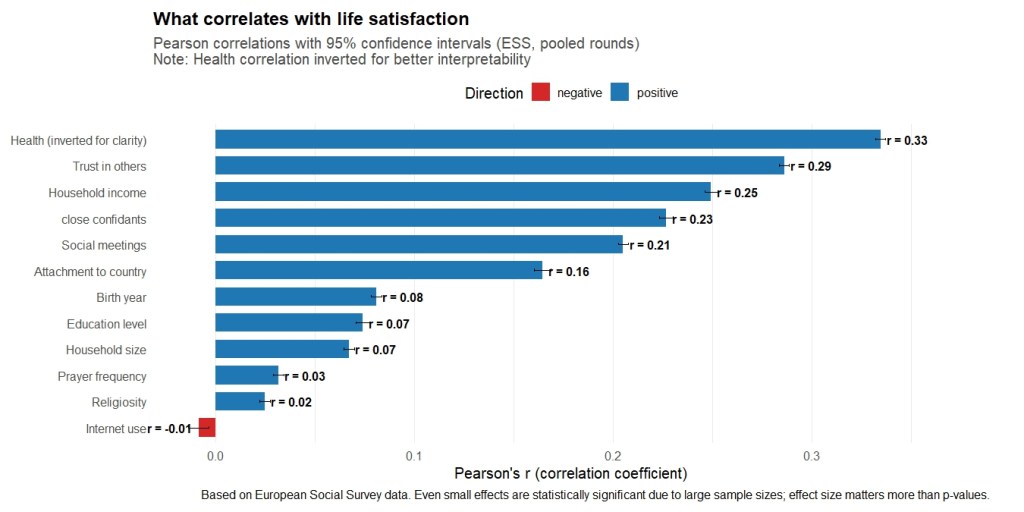

To better understand which life circumstances are associated with higher well-being, it helps to look at the statistical correlations between individual factors and overall life satisfaction. The values in the graph show correlation coefficients (r), which indicate how strongly two variables vary together.

The clearest finding: Health comes first. No other factor correlates as strongly with life satisfaction as people’s self-rated health (r = 0.33). Those who feel healthy tend to evaluate their lives far more positively. In the chart, health was reversed so that better health points rightward (positive correlation), making it visually intuitive: health is the foundation of quality of life.

In second place comes trust in other people (r = 0.29). Societies where people trust one another more tend to be happier overall, likely because trust fosters social stability, cooperation, and everyday security. This aligns with earlier research showing that social capital and cohesion are vital sources of subjective well-being. Income (r = 0.25), close personal relationships (r = 0.23), and regular social contact (r = 0.21) also show strong positive links. Together, they emphasize that life satisfaction has both material and social foundations.

Money alone does not make people happy, but financial security reduces worry, while friendship and belonging provide emotional stability. Weaker, yet still measurable, correlations appear for education, household size, and attachment to one’s neighborhood, factors that can enhance autonomy, identity, and social exchange.

Internet use has no effect on personal happiness

At the opposite end of the spectrum are only weak or slightly negative correlations, for instance with religiosity, prayer frequency, or internet use. These seem to be part of individual lifestyles, but play no central role for overall life satisfaction, at least on a European average.

Interestingly, even these small effects are statistically significant, but this is simply because of the large ESS sample size. But the key point is not significance; it’s effect size. How strong the connection truly is. And here the message is clear: Health, trust, income, and social connectedness are the true cornerstones of a satisfying life.

Across all three graphics, the pattern is unmistakable: People are happiest where they can live freely, feel secure, stay healthy, and maintain strong social ties. Political freedom provides the framework; social and economic security create stability; and trust, community, and purpose fill that foundation with life.

Perhaps that is the most important takeaway from these data: Happiness is neither a luxury nor a coincidence – it is a collective achievement. It flourishes where people not only have rights, but also the real opportunities to live well – in freedom, safety, and mutual trust. – By Maike Martina Heinrich – Nov 2025

Cover Photo: Vitaly Gariev, Unsplash

Sources:

European Social Survey

Freedom House