And Why It’s No Longer Science Fiction

Predicting crimes before they happen? For many, this immediately evokes the early-2000s film Minority Report. In the movie, so-called “precogs” foresee who will commit a crime next, allowing the police to intervene just in time. The story is set in the 2050s, yet even today machine-learning algorithms and artificial intelligence are capable of surprisingly accurate predictions. In reality, a silent web of timestamps, coordinates and routines is forming in cities around the world. A web that already reveals far more about urban life than we often realize. Every recorded incident is a tiny dot in that system. But millions of such dots form lines, structures and patterns.

To understand how far data can truly go in predicting crime today, I revisited a project that fascinated me during my data-science studies: crime prediction in San Francisco. Back then it was a methodological exercise. Today, with more recent data and better models, the capabilities, and the limits of these methods become much clearer. Data reveals that city life follows its own rhythms. Some districts “switch” to a different mode at night, as if someone flicked a light switch. Certain streets only become dangerous on particular days of the week. And some patterns appear suddenly, disappear again and still leave a trace in the data. When visualized, these patterns make one thing clear: crime prediction is not about identifying individual future offenders, but about calculating and interpreting probabilities before they turn into real-world problems.

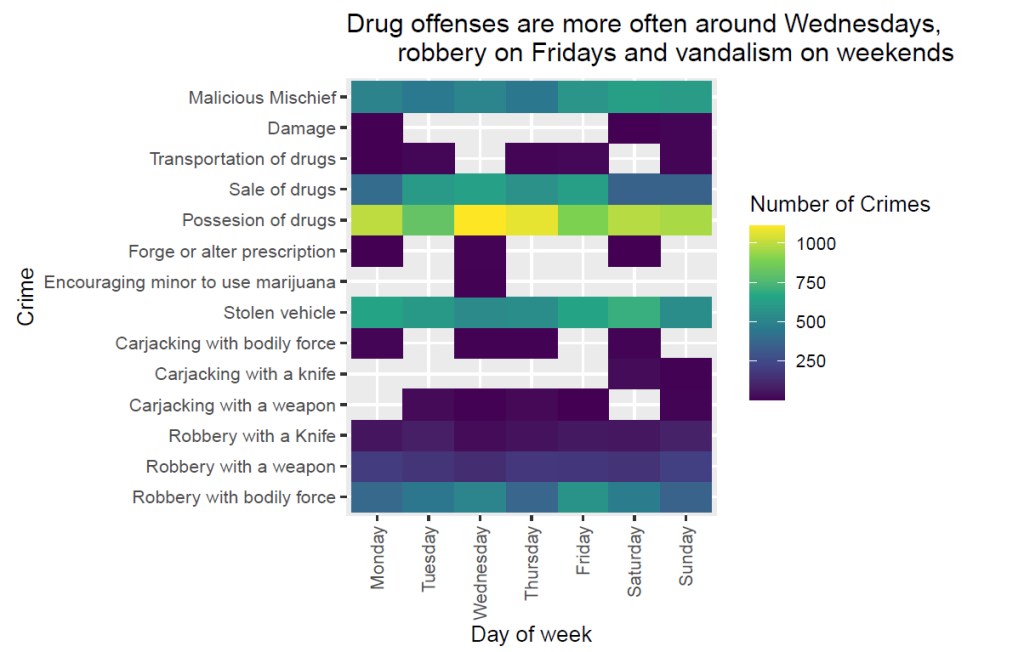

In my San Francisco project, I visualized several of these patterns. They show how crime follows temporal and spatial rhythms. The first graphic shows real data in a weekday heatmap. It reveals that some crimes follow almost a weekly schedule: certain offenses spike on Mondays, others on Friday nights, and still others mirror working hours, commuter flows or nightlife patterns.

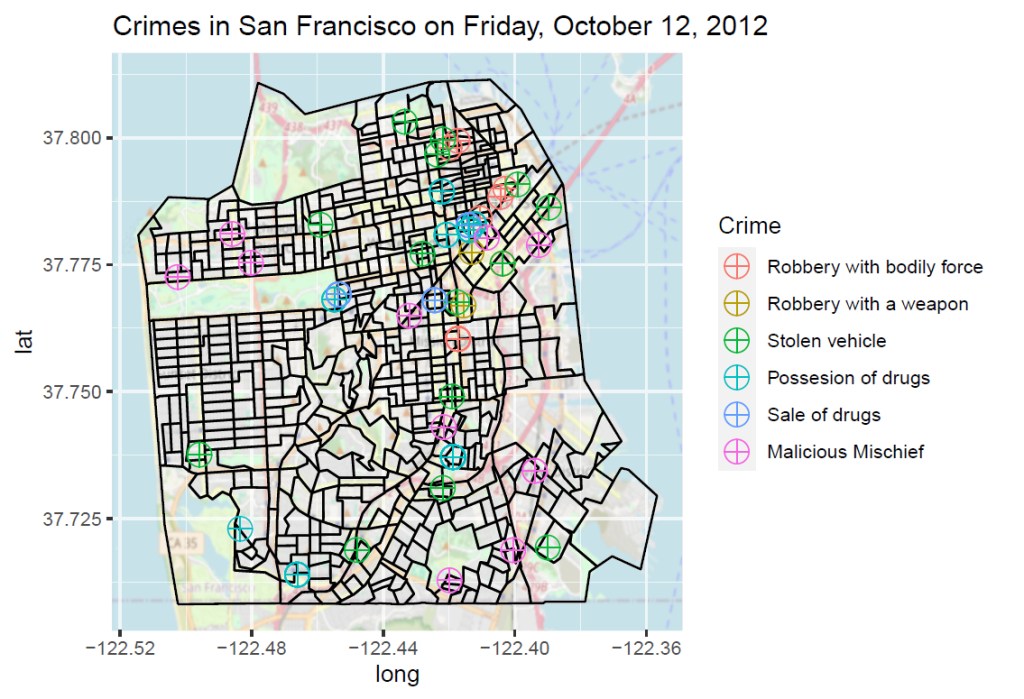

The picture becomes even more striking when looking at a single day. A city map of San Francisco shows how incidents are distributed across neighborhoods and which areas are more affected than others.

When I trained my first small machine-learning model back then, I used a Random Forest algorithm – a method built on ensembles of decision trees. Even with this simple setup, the model could predict with surprising accuracy which types of crime were likely to occur on which day and in which police district. But today’s models go far beyond such academic experiments. The systems currently being tested or already deployed by police departments detect complex patterns in real time, connect multiple data sources and adjust themselves dynamically to changing situations. Instead of only asking “How often does this crime type occur on Fridays?”, modern AI systems combine a variety of factors: lighting conditions, traffic flows, nearby events, weather, mobility patterns, weekly cycles, location characteristics and even indirect behavioral signals.

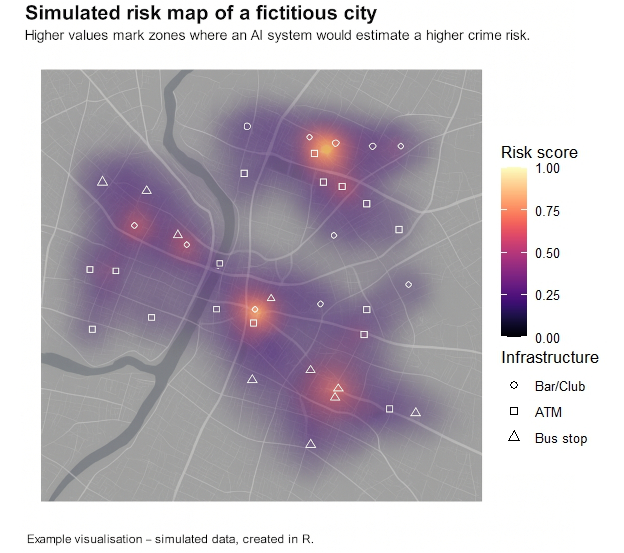

One example is Risk Terrain Analysis used in Los Angeles. Here, the AI doesn’t just detect hotspots, it calculates a spatial risk profile of the city. Features such as street lighting, proximity to bars, bus stops or ATMs are transformed into a “terrain risk” score that can change hourly.

In Tokyo, the police use AI systems that identify patterns in car thefts across hundreds of thousands of data points. The models incorporate weather, visibility and commuter flows. The result: districts receive up-to-date indicators of when and where vehicles are at increased risk.

In the United Kingdom, police forces use AI-assisted video and behavioral analysis. These systems do not look for suspects but for anomalies: unusual movement flows, rapidly forming crowds or dynamic groups that often precede outbreaks of violence. The AI identifies situations, not individuals. Yet such behavioral analysis quickly reaches ethical boundaries. Once human behavior is monitored automatically, the line between legitimate risk assessment and potential surveillance becomes blurry.

Chicago has taken a different approach. Instead of producing opaque “black-box” predictions, the city uses explainable AI (XAI). The system not only outputs a probability, it also shows why it reached that conclusion. Which variables played a role and how strongly they influenced the decision. This transparency is meant to mitigate exactly the risks that come with opaque behavioral analysis: errors, bias and unjustified discrimination.

To better understand how these modern systems work, it’s helpful to look at a visualization. Real images from operational police systems are, of course, not publicly accessible, and even if I had access, I would not be allowed to share them. To illustrate the concept nonetheless, I simulated a risk-terrain analysis myself. This visualization follows the same principles as modern systems in Los Angeles, New Jersey or Tokyo: it calculates a spatial risk score based on typical risk factors such as bars, bus stops or ATMs. The colored areas do not represent individual crimes but a probabilistic assessment, places where an AI system would recommend increased situational awareness due to the underlying urban structure.

Real systems work in a very similar way, but draw on a much broader range of data. They often include live traffic information, weather data, event schedules, historical crime trends or anonymized mobility flows. Many models update their risk surfaces every few minutes and provide interactive layers that allow officers to filter, zoom in or replay developments over time. My simulated map does not use real data, but visually it closely reflects how risk-based AI predictions look today and why they are so useful for operational planning.

While today’s systems already appear remarkably powerful, we are only at the beginning of a technological shift that will fundamentally change policing. In the coming years, AI models will not only become faster and more accurate but also more context-aware. They will be able to understand why certain places or situations become risky. At the same time, the underlying data will expand. Cities are generating more and more real-time information, from traffic data to noise patterns to anonymized movement flows. Future AI systems could learn to predict where conflicts might arise, how events shift human movement and where resources will be needed most urgently. For law enforcement, this could mean less reacting and more preventing.

But the more powerful these systems become, the more important one aspect becomes: transparency. The next generation of AI will not only need to output predictions but also explain how they were reached. Explainable AI will move from a technical option to a fundamental requirement. Otherwise society risks relying on decisions no one can fully understand.

AI can make policing more efficient, faster and more situationally aware. But it cannot replace human responsibility. The key question for the future is therefore not how accurately AI can predict crime, but how we ensure that these predictions remain fair, democratically controlled and truly serve public safety, so that dystopian scenarios like Minority Report remain nothing more than compelling fiction. The technology will continue to improve. How we use it, however, remains entirely up to us. – by Maike Martina Heinrich – Nov 2025

Title-Photo: Daniel von Appen, Unsplash

References

Caplan, J. M., & Kennedy, L. W. (2016). Risk Terrain Modeling: Crime Prediction and Risk Reduction. University of California Press.

Chicago Police Department & University of Chicago. (2018). Strategic Decision Support Centers: Data-driven policing evaluation.

Chicago Crime Lab. (2020). Transparent and accountable AI in policing: XAI pilot projects in Chicago.

Metropolitan Police Service. (2021). Emerging Technologies in Crowd Monitoring: An Overview. London.

SFPD Incidents (2012). San Francisco Open Data.

Spielberg, S. (Director). (2002). Minority Report [Film]. Twentieth Century Fox.

Tokyo Metropolitan Police Department. (2020). AI-Based Predictive Policing Pilot Study. TMPD Research Bulletin.